In the program series ‘New Democracy’ Netwerk Democratie, European Cultural Foundation and Pakhuis de Zwijger aim to investigate the building blocks for a new form of democracy. The coming months experts and changemakers from Amsterdam will be brought together to deliberate about the conditions and possibilities for democratic change.

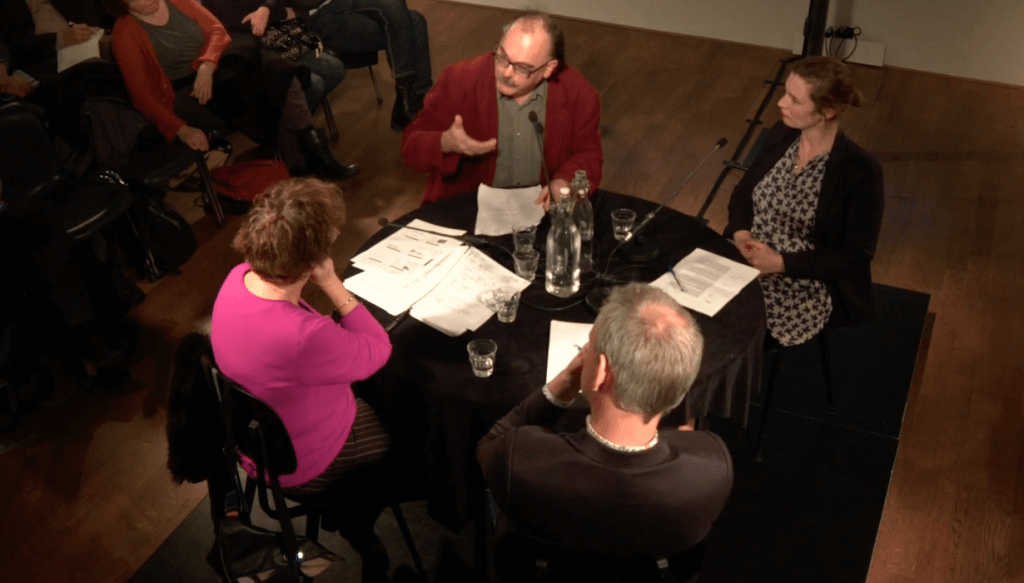

In the first evening ‘New Democracy #1: In Transition’ on 20th January a start has been made in roundtable conversation with John Grin, professor in system innovation at the University of Amsterdam, Monique Leyenaar, professor in political participation at Radboud University Nijmegen and Albert Jan Kruiter, co-founder of the ‘Instituut voor Publieke Waarden’. This evening illuminated what kind of transition our democracy is currently going through, what old principles should be retained and what new principles should be added.

What should be changed?

There is little doubt that democracy itself is still the preferred form of political organization in our current society. It is rather its ‘representativeness’ that has been put up for discussion. Where previously religion and ideologies like liberalism and socialism laid the foundation for strong political perspectives, nowadays different political perspectives within society are only loosely related to ideological foundations. However, on the political level the current multi party system still attempts to organize politics according to strong ideological differences.

The biggest problem is that the society has changed in the last decennia but the political system has remained the same –Monique Leyenaar

The multi-party system has become a field of empty containers that no longer represent the interests of citizens. Political parties seem unable to reflect the diverse interests of citizens and thus lose trust as their political representatives. Within this trend citizens are also increasingly called to take matters into their own hands in the ‘participation society’. It is however not so straightforward that these measures actually increase citizens’ capabilities. Critics of the ‘participation society’ point toward the hypocrisy of a top down policy that shifts its own responsibility onto citizens in the name of empowerment. By demanding or facilitating more participation in certain areas of society, like health care, citizens are not necessarily empowered to participate in other domains such as politics.

“As citizens we have become clients of the state, who deal with the state in the same way as a client helpdesk of a company” –Albert Jan Kruiter

One of the speakers, Albert Jan Kruiter argued that for genuine political and societal participation we need to move from an inactive and egoistic form of citizenship to a form of citizenship that serves common needs based on the idea of ‘well-understood self interest’, a term Kruiter adopts from Alexis de Tocqueville. A growing sense of urgency could provide the trigger for citizens to move from complaining to meaningful participation. So how does such urgency come about? How to shift from ‘old-thinking’ of representational politics to a new mindset focused on democratic change?

Thinking in terms of Transition

Transition is when newly formulated problems need radically different practices facilitated by new and different structures. –John Grin

According to professor in system innovation John Grin a transition towards a new system can be brought about by a co-evolution between new problems, different practices, and new structures to support these practices. For example new modes of organization such as loosely connected networks are replacing strictly demarcated communities, and there is a growing discrepancy between digital communication and traditional voting, which poses new challenges to our representative democracy. At the same time a growing bottom-up movement is introducing innovative solutions that are functioning parallel to regular practices of governance. These new practices such as de-centralized organization of healthcare like ‘Buurtzorg’, cooperative assurances like the ‘Broodfonds’, and citizen summits such as the G1000 show how citizens experiment with alternative ways of taking up societal responsibility. So which structures could support these new practices to grow into new modes of political participation? Three core principles for a new democracy were formulated during the roundtable conversation.

- Subsidiarity

“In a too big democracy where one needs bureaucracy in order to be accountable one loses democratic experience and well-understood self interests. I think the decentralization of national government towards a fiscal autonomy of the municipality is the first step to locally strengthen the democracy” –Albert Jan Kruiter

The principle of subsidiarity is central in order to replace the vertical structure of decision making in the current representative democracy with a more horizontal structure of decision making. According to the principle of subsidiarity social problems should be dealt with by those who are nearest to its solutions. By decentralizing power and eliminating unnecessary intermediaries new practices of citizens could become part of a more direct form of governance. Here the representative system is replaced by a system of local participation.

- The value of diversity

The transition in democratic structures also involves a shift in values. From a neoliberal perspective focused on efficiency and the individual we are moving to a new focus on quality and a multi stakeholders’ perspective.

Direct democracy is different from representative democracy because of a shift from representation to participation. Representation loses its traditional meaning and is replaced by the participation of different stakeholders, and different communities that through their self-interest encourage the common interests of society. Central to participation compared to representation is diversity.

“In such a transition there are always some frontrunners who bring about change. In this sense inequality can be an advantage that we should value instead of uniformity” -Eisse Kalk

In a new democracy inequality and the diversity of stakeholders are not a weakness but in fact can contribute to the strength of the system. In his book ‘Tegen Verkiezingen’ David van Reybrouck proposes a balloting system that appoints randomly chosen citizens to governmental positions as a way to use diversity to redefine the representative democracy. In this way a democratic system can be created in which self-interest can genuinely be translated into common interest. Such a balloting system or ‘citizens’ jury’ could work to realign on the one hand the discourse of the welfare state focused on production and equal redistribution with the discourse of the bottom-up movement that is more concerned with issues of sustainability, integration and social cohesion. According to John Grin these new challenges call for a political system that exchanges a commitment to uniformity with a commitment to a diverse set of interests.

- Checks and Balances

The question arises in how far the current democracy should be replaced by new structures. Does this democracy have the right to cancel itself? The answer is that not the complete system of democracy should simply be pushed into revision. There are important aspects of the current democracy that should remain central in any new form of democracy. Most important is the current democracy’s structure of checks and balances in which power is divided over several institutions. We should thus also realize what we do value in the current democracy.

“If there is anything in the transition of our democracy that we should preserve this would be our current principle of checks and balances” –Albert Jan Kruiter

Currently the separation of power is constitutionally secured and this should remain so when thinking about a new form of democracy. In the transition to a new democracy attention should thus be paid to existing and new forms of checks and balances.

Local participation compared to a representative party system, diversity compared to uniformity, and the recognition of the core principles of democracy. These principles form the guidelines for the transition of our democracy.

Watch the video of this evening:

https://vimeo.com/153235723